Published on: February 4, 2024

| CQS, in collaboration with Earki, conducted research on the dissemination of disinformation during the General Election of Bangladesh 2024. The study was led by Professor Dr. Sumon Rahman and Senior Fact-checker Shuvashish Dip. It also involved contributions from Research Assistants Ishmam Rahim Kareeb and Yuvraj Sen from CQS. |

Introduction

Disinformation appears to be a prevalent strategy in electoral campaigns, with potential consequences such as confusion among voters, reduced turnout, amplified voter confusion, social cleavage, marginalized population disenfranchisement, and erosion of trust in democratic institutions (n.d.). The year 2024 is pivotal for democratic elections globally, with an estimated participation of nearly half the world’s population, spanning various countries, including the United States. In South Asia, four major elections, including those in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, are anticipated (Hsu et al., 2024), (Ewe, 2023). As Bangladesh has recently concluded its general election, there is an opportunity to investigate the occurrence of disinformation on social media during this electoral process. This study aims to analyze social media-based disinformation trends throughout the election period and to understand the novelty and momentum these attempts to create. Our primary objectives are to the prominent themes of election-related disinformation and identifying the targeted individuals or institutions in these campaigns.

The 12th general election in Bangladesh transpired on January 7, 2024, resulting in the victory of Bangladesh Awami League (BAL),, securing the government for three consecutive terms. Sheikh Hasina now holds the distinction of being the longest-serving prime minister in Bangladesh and the world’s longest-serving female prime minister (Sheikh Hasina: Longest Serving Female Prime Minister, n.d.). However, controversies surround this election, as the major political party BNP (Bangladesh Nationalist Party) boycotted it, deeming it non-participatory. Allegedly, the ruling party contested some seats with their own party members posing as independent candidates. The Election Commission reported a total voter turnout of approximately 41% (Suhrawardy, 2024).

Methodology

This is an exploratory study centered around disinformation circulating on social media during the election period in Bangladesh. Our data collection spanned from November 15, 2023, when the Election Commission unveiled the election schedule, to January 7, 2024, the election day. During this critical period, Bangladesh witnessed various political campaigns both in favor of and against the election.

Our unit of analysis comprises fact-checking reports, specifically content debunked by professional fact-checkers (PFC) in Bangladesh. We gathered content from four fact-checking organizations: Fact-Watch, AFP, Boom Bangladesh, and Rumour Scanner. These organizations were selected as they are signatories of the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN), ensuring the delivery of high-quality reports adhering to specific guidelines.

The study focused on content from social media, particularly Facebook, which holds a dominant position with 93.64% of the market share in Bangladesh (Social Media Stats Bangladesh | Statcounter Global Stats, n.d.).

A total of 200 fact-checking reports were collected during the specified timeline. To eliminate duplications, we identified and separated 157 unique contents based on specific types of Facebook posts. Since similar claims were found with different post types and multiple claims within a single post, our analysis focused solely on individual posts.

The dataset was then categorized into five main divisions: content type, topic, targeted individuals and institutions, channels used for dissemination, and techniques that have been used. Content was classified based on the medium, leading to the creation of a content type category. Prevalent issues were identified by examining the topics covered in these contents. Finally, we determined the individuals and institutions targeted by analyzing the content.

Findings

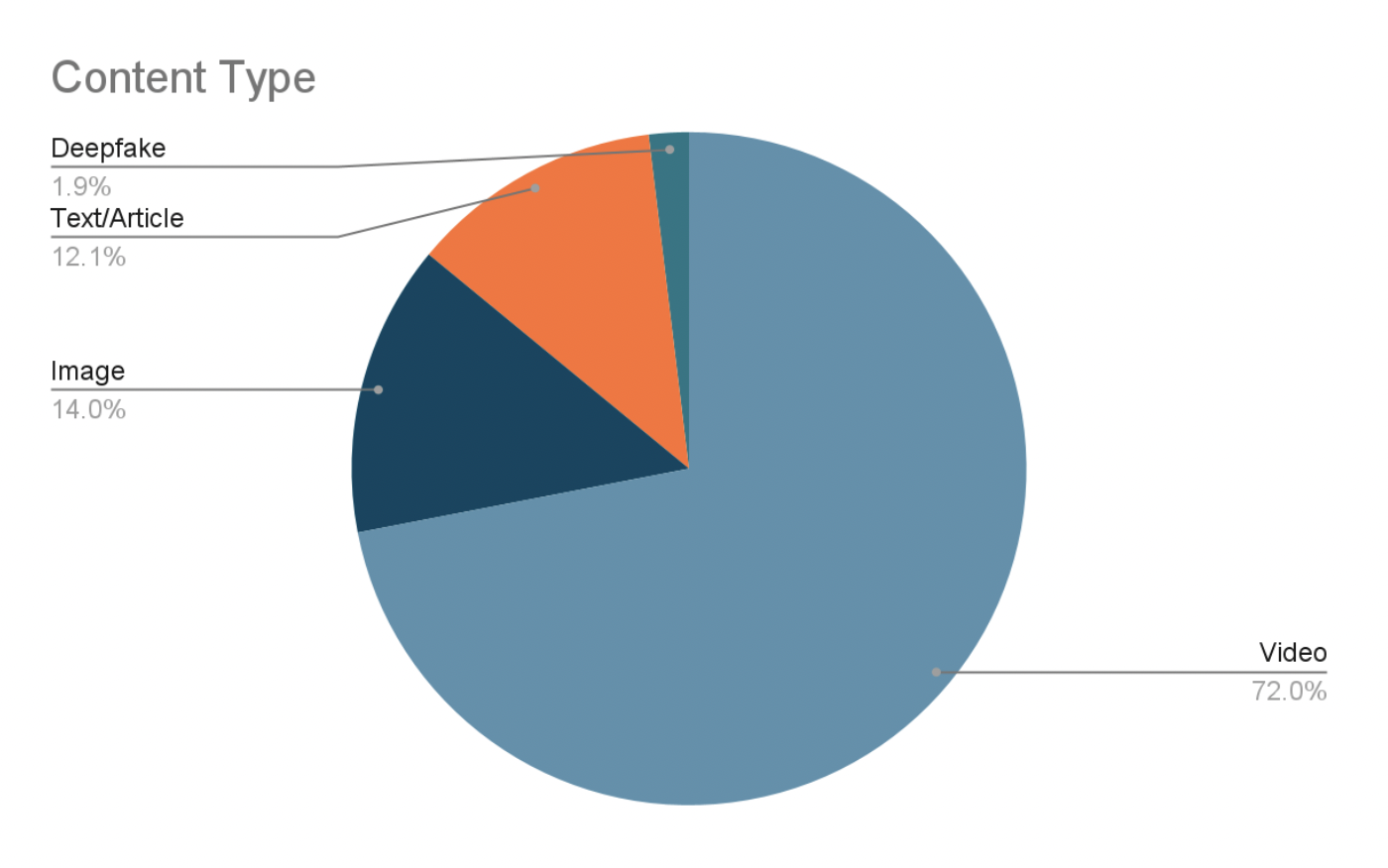

What types of content?

Our findings revealed four types of content used in disinformation campaigns – video, image, text, and deep fakes. Video emerged as the predominant medium, constituting 71.9% of the total contents. Videos often utilized thumbnails to convey their claims, sometimes accompanied by voiceovers, and frequently compiled unrelated video clips to fabricate claims.

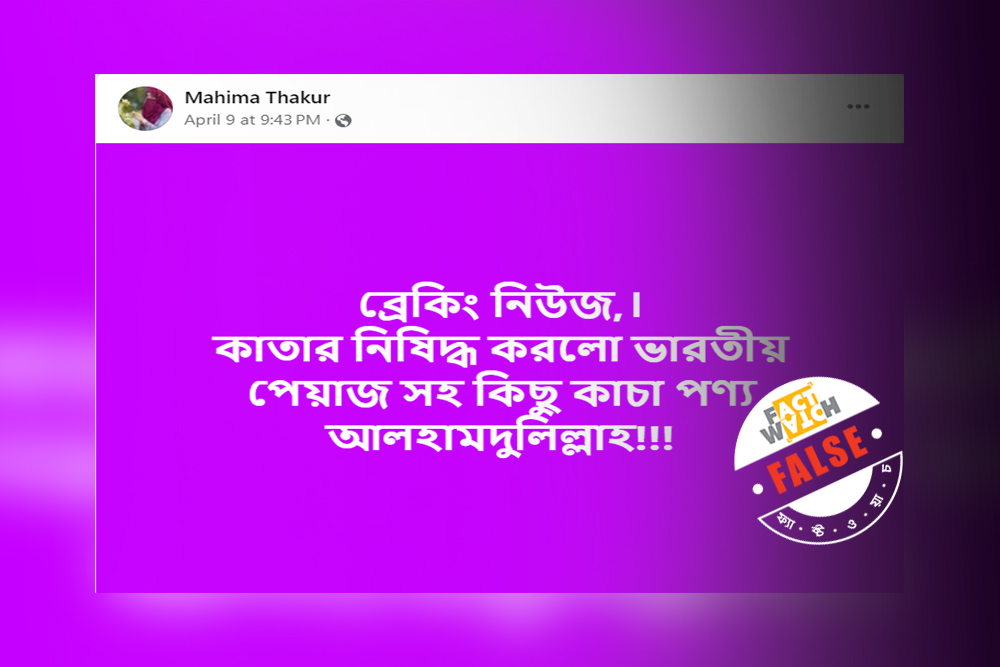

Images accounted for 14% of the total contents, with disinformation often involving the manipulation of photocard (kind of images that reputable media houses use) or fake circulars attributed to various political parties and government entities.

Text-based content, including links to news articles, constituted 12.1% of the fake claims. These claims were disseminated through Facebook status or other media, relying solely on caption-generated content.

Al (Artificial Intelligence) is gaining significant momentum to spread disinformation across the world, although the Bangladesh election has witnessed only a few. We have also identified some disinformation using artificial intelligence. There were three specific deepfake videos which is 1.9% of the total disinformation content have been found. Deepfake is a type of artificial intelligence that is used to re-create convincing images, audio and video (Barney & Wigmore, 2023).

There were a few incidents of fake audio circulated on Facebook, claiming to be “disclosed call records” of some politically significant persons. However, these did not get viral in terms of their circulations, hence were not picked up by fact-checkers. Since this study did not extend its sampling beyond fact-checking reports, the audio recordings were not considered as significant.

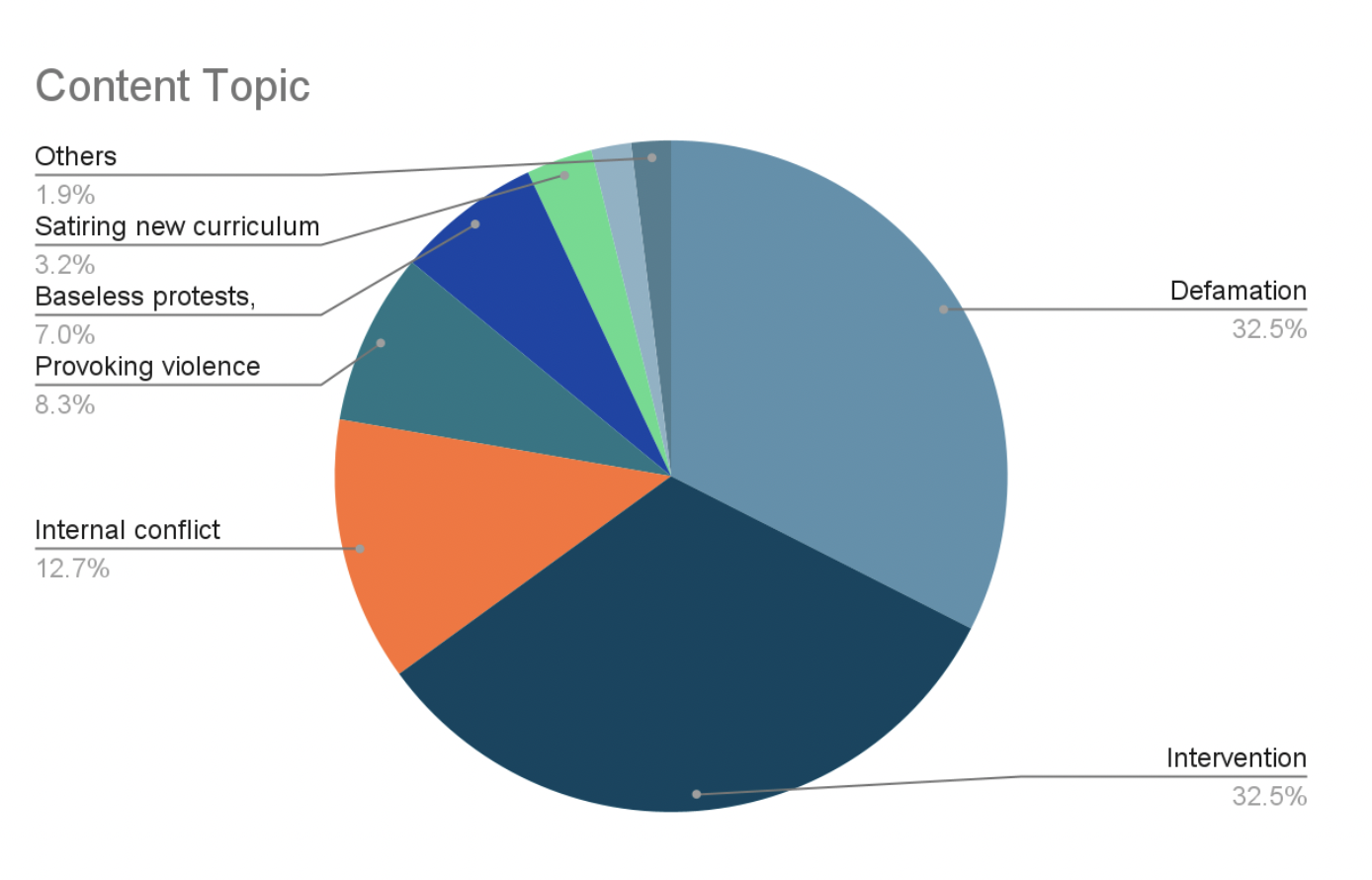

What are the topics?

We have categorized prevalent issues of election disinformation into eight distinct categories, each based on specific content characteristics.

Defamation: A significant portion of the content (32.4%) centers around defaming political figures or parties. These contents often target the individuals or organizations, employing baseless lies or misleading information such as, the ruling party being a puppet of India, false or old incidents of arrests, false slogans, individuals going against their own party commands, individuals absconding offices, and so on. These are categorized under the umbrella of “defamation” as the intention of these content is clearly to downsize one’s image.

Intervention: Another prominent category (32.4%) encompasses content focusing on interventions related to elections, involving foreign stakeholders, military, and civil society members. Sub-categories include foreign intervention (such as, the US imposing visa sanctions to ruling party officials and bureaucrats), military intervention (such as, the military taking over), and civil society intervention (such as notable civil society members urging for caretaker government). The majority of these contents make ungrounded claims and utilize manipulated images and videos.

Internal conflicts: Content in this category (12.73%) portrays tense situations within a political party’s own members. These contents highlight historical tensions among party members, often reviving old issues with a new perspective.

Provoking violence: Approximately 8.2% of the content focuses on provoking violence. These contents typically utilize older video clips depicting political violence, falsely asserting that such events are currently unfolding and calling for action.

Baseless protests, releases, arrests, illnesses, and deaths: This category (7%) encompasses content spreading baseless claims about political movements, releases of arrested leaders, new arrest incidents, physical illnesses of candidates or political leaders, and fake death hoaxes. Contents often use older videos or images while falsely presenting them as recent events.

Mocking new curriculum: This specific type of content constitutes 3.1% of the total. It targets the new education curriculum declared by the Ministry of Education for primary and higher secondary education. These contents mock the decision from a predominantly religious perspective, attempting to influence public perception against the government and the ruling political party.

Financial mayhem: About 1.9% of the content aims to create panic about a financial mayhem within the country. These Facebook posts primarily target financial institutions and some government entities.

Others: A small percentage (1.9%) of contents lack a specific focus and involve inconsequential disinformation, typically using unsophisticated visual content.

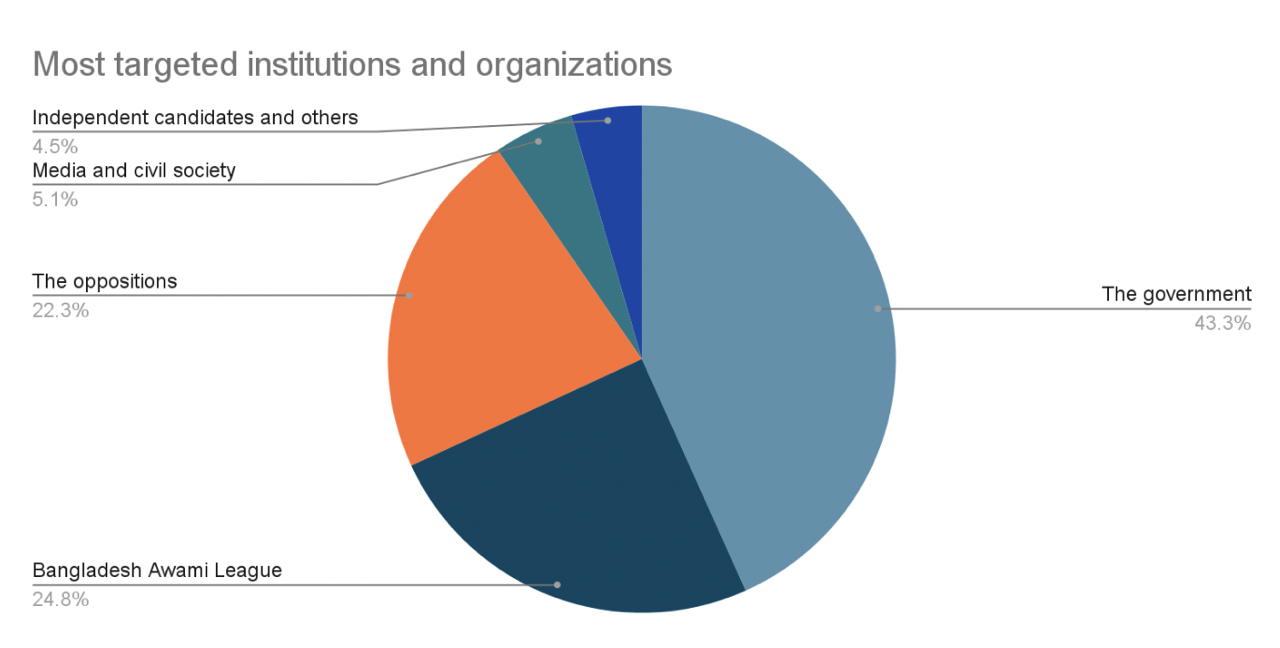

Who are the targets of disinformation?

As explored, the disinformation campaigns have been seen to target several institutions and organizations of Bangladesh, and these can be categorized in four distinct groups: the government, Bangladesh Awami League, the opposition parties including BNP, media and the civil society. Apart from these, some individuals are also targeted by these campaigns who are loosely aligned with any of the groups above. But the study considers them as individuals too, since their affiliations with these organizations are not well-formalized.

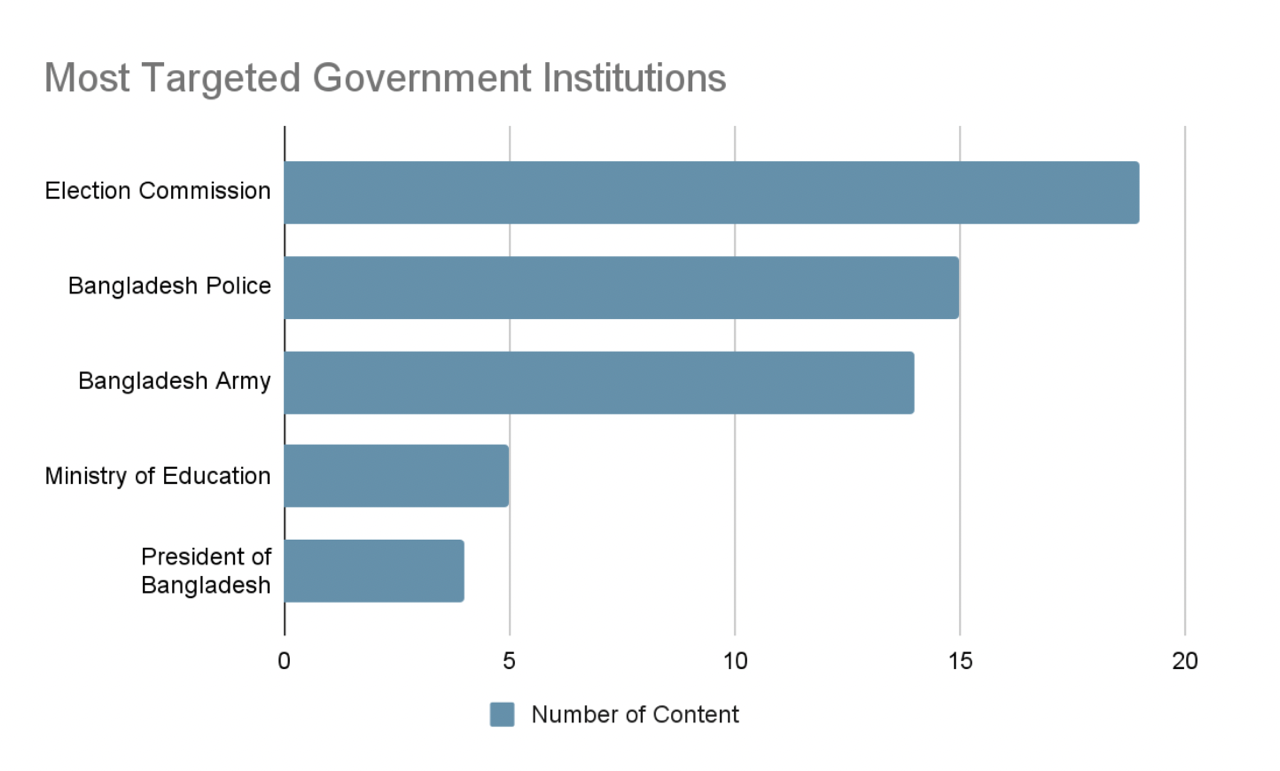

The government: More than 43% of the total content of disinformation targeted the government institutions and organizations during the election period. Notably, the Election Commission and its chief election commissioner were frequently targeted. The main message circulated was that the EC postponed or canceled the election, or seeked a public apology for trying to conduct an “unfair” election, etc. In addition, government bodies such as Bangladesh Police and Bangladesh Army were equally subjected to many disinformation campaigns. They appeared as agents of intervention (to stop the election or to take over the power) in those contents. The President of Bangladesh, various ministries, and Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) were also among the entities targeted.

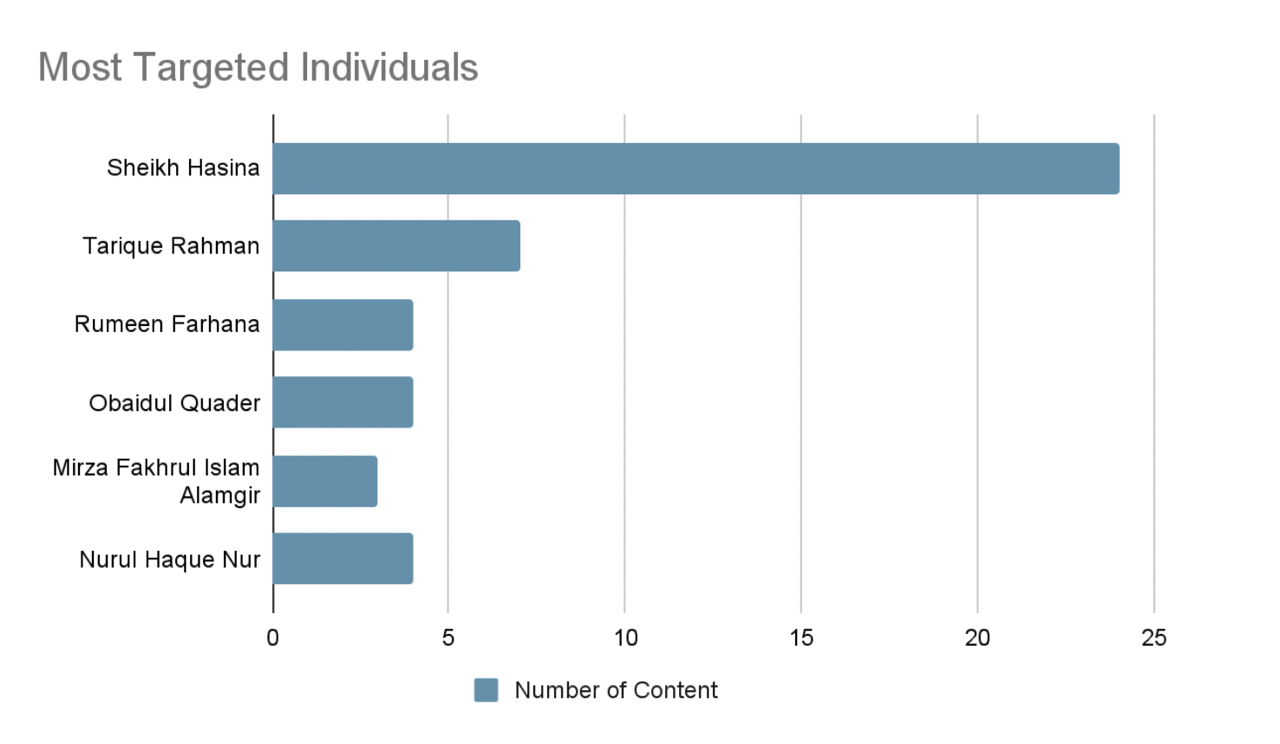

Bangladesh Awami League: As much as 24% of the content targeted Bangladesh Awami League which made them the most targeted political party in the election disinformation. Political leaders of BAL, particularly the Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, were extensively targeted. The remaining content focused on other party leaders and organizations affiliated with BAL. The issues circulated were mainly conflict between party members, rumors of visa sanctions, fake arrests, protest against election by various stakeholders, etc. The main thematic concentration of the disinformation content against BAL can be categorized as “defamation” and “intervention”.

The oppositions: Combined, the opposition political parties were targeted in almost 22% of the contents, with BNP being the primary focus. Among the targeted individuals within BNP were Tarique Rahman, Vice Chairman of the party, Khaleda Zia, former Prime Minister and Chairperson of the party, Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir, Secretary-General of the party, and Rumeen Farhana, a prominent party leader. Other opposition entities, including Jatiya Party, Nurul Haq Nur, a Bangladeshi activist and politician, and Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami, were also subject to disinformation.

Media and civil society: A significant circulation of photocards, utilizing mainstream media identities, played a role in disseminating disinformation, comprising 5.1% of the total content. Furthermore, fake quotes attributed to various civil society members, such as Dr. Yunus and Salimullah Khan, were circulated as part of the disinformation campaign.

Independent candidates and others: About 4.5% of the total content targeted independent candidates in the election and other political members who did not attend. Individuals such as Mahiya Mahi, Syed Sayedul Haque Suman, Nixon Chowdhury, and Murad Hasan were among those subject to disinformation campaigns.

What are the Facebook channels used?

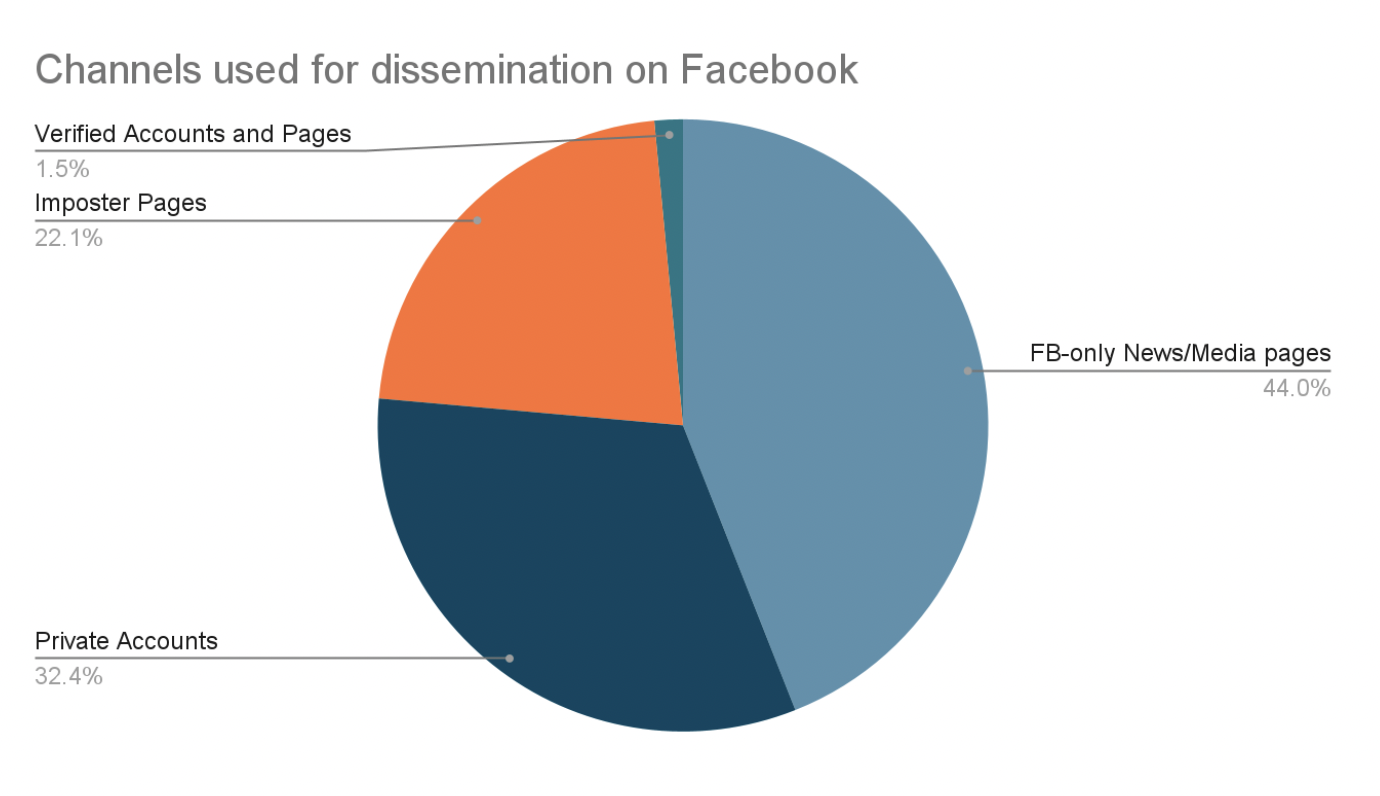

We conducted an investigation to trace the origins of disinformation circulation and categorized them into four main groups: Private Facebook Accounts, Imposter Facebook Pages, Facebook-only News/Media Pages, and Verified Accounts and Pages. Private Facebook Accounts include both authentic and fake profiles, as we were unable to verify their authenticity. Notably, we identified Facebook pages impersonating politicians and individuals with verified accounts, labeling them as imposter Facebook pages. Another category comprises self-proclaimed Facebook news/media company pages lacking valid certifications. The final category involves verified accounts and pages. However, our study encountered limitations, as we couldn’t identify all channels due to their deletion after fact-checking. We gathered the overall count of channels and calculated their percentages to understand the frequency of each channel’s usage.

Facebook-Based News/Media pages emerged as the primary disinformation channel (44%), followed by private Facebook accounts at 32.4%, imposter Facebook pages at 22.1%, and verified accounts and pages at 1.5%.

Techniques used for dissemination

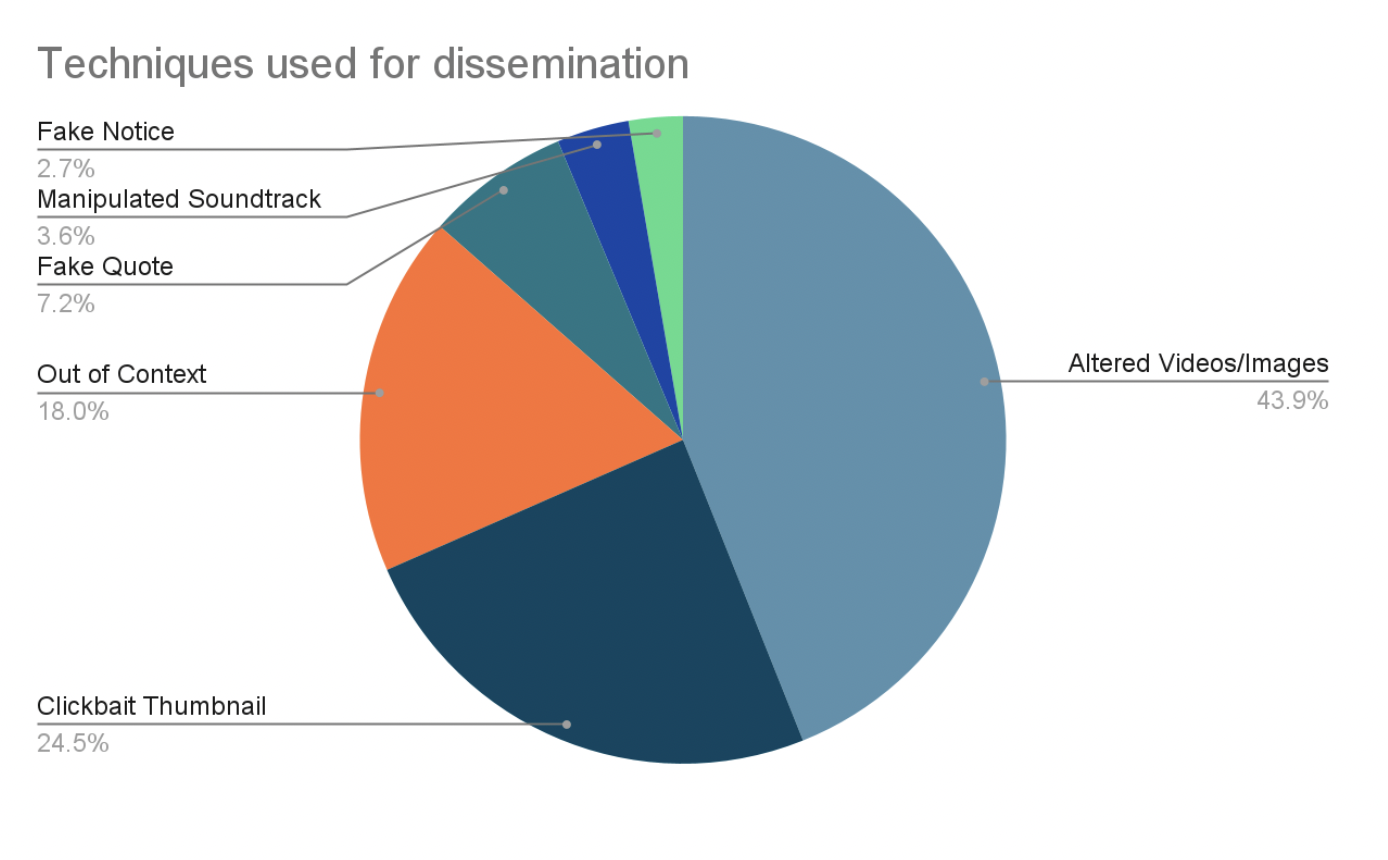

We sought to examine the techniques employed in disseminating disinformation, categorizing them into seven distinct categories: Altered Videos/Images, Out of Context, Clickbait Thumbnail, Manipulating Soundtrack, Fake Quote, Fake Notice, and Deepfake. We gathered the overall count of techniques and calculated their percentages to understand the frequency of each technique’s usage.

Altered Videos/Images: A common pattern emerged, with this particular technique employed 43.9% of the time, involving digitally altered videos or images to substantiate claims. Notably, some images were manipulated to tarnish the reputation of political parties or individuals, while videos often comprised compilations of old or out-of-context footages.

Clickbait Thumbnail: Employed 24.5% of the time, this technique features thumbnails with claims unrelated to the main incident, exaggerated to entice audience clicks.

Out of Context: Used in 18% of the time, this technique circulates different incidents as recent ones, often omitting specific details to mislead audiences.

Fake Quote: Utilized in 7.2% of the time, this technique employs names of influential figures, such as civil society members or politicians, to propagate messages under their authority.

Manipulated Soundtrack: In 3.6% of the time, video soundtracks were manipulated to align with desired claims, involving changes to background music and the insertion of different audio.

Fake Notice: Used in 2.7% of the time, this technique involves copying the design of authentic political party press releases, altering dates and main messages to convey misleading claims.

Discussion and conclusion

As we have seen through the fact-check reports, the election period did not add any new dimension to the existing disinformation ecosystem, except for a few amateurish deepfake videos. Despite the fact that deepfake videos have become very handy these days, it is surprising not to see much investment in this technology during the election period. Even the other disinformation campaigns did not carry very significant messages that can ignite harm and violence. Not much provocation was seen against the religious and ethnic minorities as well. In terms of numbers, the amount of disinformation during this period was not very significant. Among the techniques, the use of photocards and fake quotes remain predominant, and clickbait thumbnails are frequently used to attract the audience.

Why did the disinformation-producers not find any momentum during the election of Bangladesh? This might be a little out of scope for the current research, but we can justifiably assume that this has something to do with the nature of the election where the main opposition party did not participate. With BNP boycotting the election, the outcome became a very predictable one, therefore the main political energy was channeled to defame each other and to ring the alarm of foreign and military interventions. This is the reason why content related to “defamation” and “intervention” gets prominent, and categories like corruption, violence and financial mayhem get less attention. One of the main strategies of disinformation in this election was faking endorsement of different stakeholders: such as false quotes from the US President, UN Secretary General, Civil Society members and powerful bureaucrats, targeting political stakeholders of either side. This is quite a relief for the information ecosystem that the disinformation landscape did not go beyond and found ways to create more harm and violence. The disinformation ecosystem has thus lost its color alongside the political movement for the caretaker government which also lost its momentum in Bangladesh, and instead both were opting for “intervention” of actors outside the local political milieu. Except for such an “intervention” which is proven to be myth later on, none of the stakeholders were seen to have been significantly interested in influencing public opinion, either by truthful or false information. This is what has made the entire election disinformation ecosystem less influential and insignificant.

Bibliography

- W. (n.d.). Disinformation, Social Media, and Electoral Integrity. National Democratic Institute.

https://www.ndi.org/disinformation-social-media-and-electoral-integrity

- Hsu, T., Thompson, S. A., & Myers, S. L. (2024, January 11). Elections and Disinformation Are Colliding Like Never Before in 2024. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/01/09/business/media/election-di-

sinformation-2024.html

- Ewe, K. (2023, December 28). The Ultimate Election Year: </br>All the Elections Around the World in 2024. TIME.

https://time.com/6550920/world-elections-2024/

- Sheikh Hasina: Longest Serving Female Prime Minister. (n.d.). GorakhaPatra.

https://risingnepaldaily.com/news/37423

- Suhrawardy, M. A. A. F. (2024, January 7). CEC: Voter turnout 40% across Bangladesh. Dhaka Tribune. https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/ele- tion/336129/cec-voter-turnout-40%25-across-bangladesh

- Social Media Stats Bangladesh | Statcounter Global Stats. (n.d.). StatCounter Global Stats.

https://gs.statcounter.com/social-media-stats/all/bangladesh

- Barney, N., & Wigmore, I. (2023, March 21). deepfake Al (deep fake). Whatls.

https://www.techtarget.com/whatis/definition/deepfake